The Crimes and Punishments of Society: Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia

Out of the fourteen million HIV-positive patients documented worldwide, in 1993, two and a half million were diagnosed as AIDS cases. These statistics are tangible evidence that explain society’s fear and concern about the looming epidemic in the 1980’s and 1990’s that caused various stigmas and fostered so much discrimination. Jonathan Demme’s 1993 film Philadelphia explores the moral and ethical issues manifested by AIDS and its relation to homosexuality. This drama suggests AIDS was viewed as a crime against the self and society as a whole. The film depicts people who believed punishment was the only viable resolution for the promiscuous conduct associated with AIDS. These symbols were also discussed in Susan Sontag’ s essay “AIDS and its Metaphors.”

After viewing Philadelphia in class, I thought it would be interesting to read the script in order to analyze the director’s notes and commentary. In studying Demme’s intentions for the scenes, I was able to better understand the language and relationships between the actors. I found many intriguing pieces of dialogue I had originally missed; for instance, Joe Miller is often seen in the background advertising his law firm with the line, “if you or someone you know has been injured through the fault of others, you may be entitled to legal remedy.” Andrew’s laughter after watching Miller’s commercial in the hospital is an ironic reaction to a statement that questions guilt or innocence among the ill. Joe essentially says that if your suffering has been caused by anyone other than yourself, you may be eligible for legal solutions. Does this imply that those suffering from illness or accidents can be deemed guilty and, therefore, deserve the outcome of their actions making them unworthy of legal aid? During one of the initial court scenes, Judge Garnett remembers Miller because of the latter’s television commercial. In Demme’s original script, the judge suggests that Miller change the wording from “the fault of others” to “the negligence of others.” It is essential to remember the various meanings of the word negligence in legal terms. This word often means general inattentiveness, but in this case it could refer to irresponsible actions a person should avoid. This conversation might be a clever way to incorporate the sense of guilt that AIDS victims who give the disease to others ought to feel.

This image of AIDS as a crime is also depicted in Sontag’s essay “AIDS and Its Metaphors,” which opens by introducing society’s use of military symbolism to describe illness as an invasion against the body, and our efforts to stop the spread of the disease as a war. Military imagery often implies the use of force and violence. In her essay, Sontag suggests that society judges the ill and labels them as guilty or innocent. She states, “Victims suggest innocence. And innocence, by the inexorable logic that governs all relational terms, suggests guilt” (Sontag, 99). Sontag asserts that society describes AIDS in two ways. The actual illness is seen as an invasion, but when the focus is transmission,a different image is invoked: “pollution” (Sontag, 105). This view creates a divide between the healthy population and those who endanger their purity with the chance of infection – or “pollution,” as she refers to it. Two scenes in the film directly portray this segregation of healthy persons from the ill. One scene involves Beckett being called into the conference room by his partners. Demme utilizes pauses and camera angles to show the obvious separation between Beckett’s seat and where his employers are lined up. The distance between them quietly displays the true feelings of the law firm, thus setting the scene for firing Beckett. Demme creates tension here that is strong enough for the audience and Beckett to sense. The manufactured divide between society and AIDS victims is clearly shown through the judgmental stares of the lawyers while they assume promiscuity and homosexuality on Beckett’s part as the cause for contracting AIDS.

The two main behaviors linked to the transmission of AIDS are homosexuality and illegal drug use. Both actions were condemned by society during the time Philadelphia was produced and when Sontag’s essay was published. Sontag describes AIDS as “indulgence, delinquency—addictions to chemicals that are illegal and to sex regarded as deviant” (Sontag, 113). During the initial outbreak of AIDS, society was not only dreadfully afraid of contracting the disease itself, but worried about the possible transmission of sins attached to the illness. This concern is seen in the film when Beckett meets with Miller at his office to request legal assistance. Upon arriving, they appear to share a mutual respect until Beckett tells Miller that he has AIDS. Miller immediately tries to physically separate himself from Beckett and becomes obsessed with retracing every action Beckett has made and noting what he has touched. Instead of focusing on facial expressions and verbiage, Demme uses the camera to focus on objects Beckett has touched, pausing briefly to see the judgmental skepticism on Miller’s face. This is an interesting scene that shows the uncertainty people confronted with the reality of AIDS experience.

Unlike many diseases, AIDS does not seem to strike random individuals, but instead, is thought of as a consequence to one’s actions. Given that AIDS is sexually transmitted, it is effortless to connect the disease to images of a plague, one that is sent as punishment against those exhibiting deviant behavior. One main problem portrayed in the film was society’s lack of empathy towards those infected with AIDS, due to the promiscuous actions often associated with the illness. In the film, there is a scene where Miller vents to his wife about his views and confusion regarding homosexuality. He points out that the case is more about discrimination against homosexual people than it is about illness. He seems to realize that the opinions of the society and of the family he was raised in contribute to the feelings he now has towards the gay community. The stigmas and actions attached to AIDS often engross people to the point where they forget to empathize with those who are ill. These actions were frequently viewed as criminal injustices against the norms and values of society. During the initial outbreak of AIDS,the majority of people viewed homosexuality as a crime against what nature intended. Many religions believe that homosexuality is to be regarded as an act of sin, deserving of punishment. Consequently, AIDS was viewed as punishment for the immoral conduct that an individual chooses to pursue.

The judgment of innocent versus guilty victims can be observed during one of the courtroom scenes from the film. While defending Beckett’s case, Miller calls a woman in her mid-thirties to the stand. At first glance, she appears to be in good physical and mental health. We quickly learn this is not the case when Miller asks her if her colleague Walter Kenton knew that the lesions on her face were caused by the AIDS virus. She describes how she blatantly told the partners about her illness because she had nothing to lose. Miller’s next asks if Kenton treated her any differently after he attained knowledge of her illness. The witness says that aside from his face expressing disgust and, possibly, a fear of being contaminated, he never gave her direct trouble regarding AIDS. Miller asks if she was fired or asked to leave by the law firm, and she asserts that she was never approached in that manner. In fact, she was allotted time off for medical reasons whenever necessary. After the witness describes how she contracted the illness —through a blood transfusion — the defense then labels her an “innocent victim of the AIDS tragedy.” She refutes this statement, insisting she is no different from anyone else suffering from the disease. She says: “I’m not guilty, I’m not innocent. I’m just trying to survive.” This is an obvious example of society trying to pin a label on people according to their actions instead of their current circumstances. The defense hopes to convince the jury that this woman was open with the firm about her illness, and contracted AIDS innocently. In contrast, Beckett sought to cover up his illness, which he had acquired promiscuously.

In comparing Kenton’s treatment of both AIDS victims, we can conclude that he was not only morbidly afraid of contracting AIDS, but he was more fearful of the moral implications attached to the transmission of the disease. The entire firm feared Beckett because of the stigma attached to AIDS and, ultimately, to homosexuality. Kenton personally justifies labeling Beckett as a guilty victim of his own actions who deserved punishment for his negligence. In this case, AIDS is seen as a crime against the body and soul of the sufferer caused solely by that individual’s actions and choices. Society often strips illness of its true medical value in order to rationalize the horror presented by the sufferers.

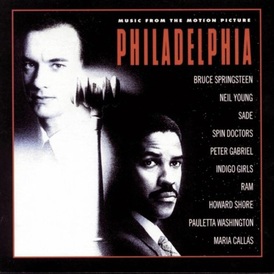

This idea of AIDS as a crime against the self raises a doubt of guilt and shame for those ill persons. Sontag asserts that with “AIDS, the shame is linked to an imputation of guilt” (Sontag, 112). The haunting song “Philadelphia,” performed by Neil Young, alludes to the struggle regarding the disgrace and culpability AIDS victims feel. The lyrics read, “when the secrets came unfurled/ Tell me I’m not to blame/ I won’t be ashamed of love.” This statement captures the sentiment and struggle a homosexual may encounter when his identity is revealed because of the physical characteristics his disease makes publicly visible. He wants to be told it’s not his fault, because he does not want to be ashamed of who he is, and how he conducts himself. Sontag discusses the unveiling of an AIDS victim’s sexual preference by saying “the illness flushes out an identity that might have remained hidden” from society, had they not contracted the disease (Sontag, 113). Clearly in this film, AIDS was the factor that revealed Andy Beckett’s homosexuality.

In viewing AIDS as a crime that deserves punishment, we connect the themes of this illness to greater concepts of human nature. People have always investigated sin, crimes against society, and issues with identity. All of these concerns can be found in the ways society views and stigmatizes AIDS. The film Philadelphia uses a full spectrum of emotions, images, and metaphors to discuss homosexuality and AIDS during the nineties. Among the moral and ethical issues raised in the film, punishment for supposed guilt is a common theme. This worldwide epidemic made people very much afraid of contracting AIDS and becoming exposed to the various stigmas and discrimination associated with this illness. The film Philadelphia clearly demonstrates this proposition.

And here is a link to Neil Young singing the song “Philadelphia,” that I discussed above.